2015 Stanford Rape Case Supports Link Between Excessive Alcohol Consumption and Sexual Assault

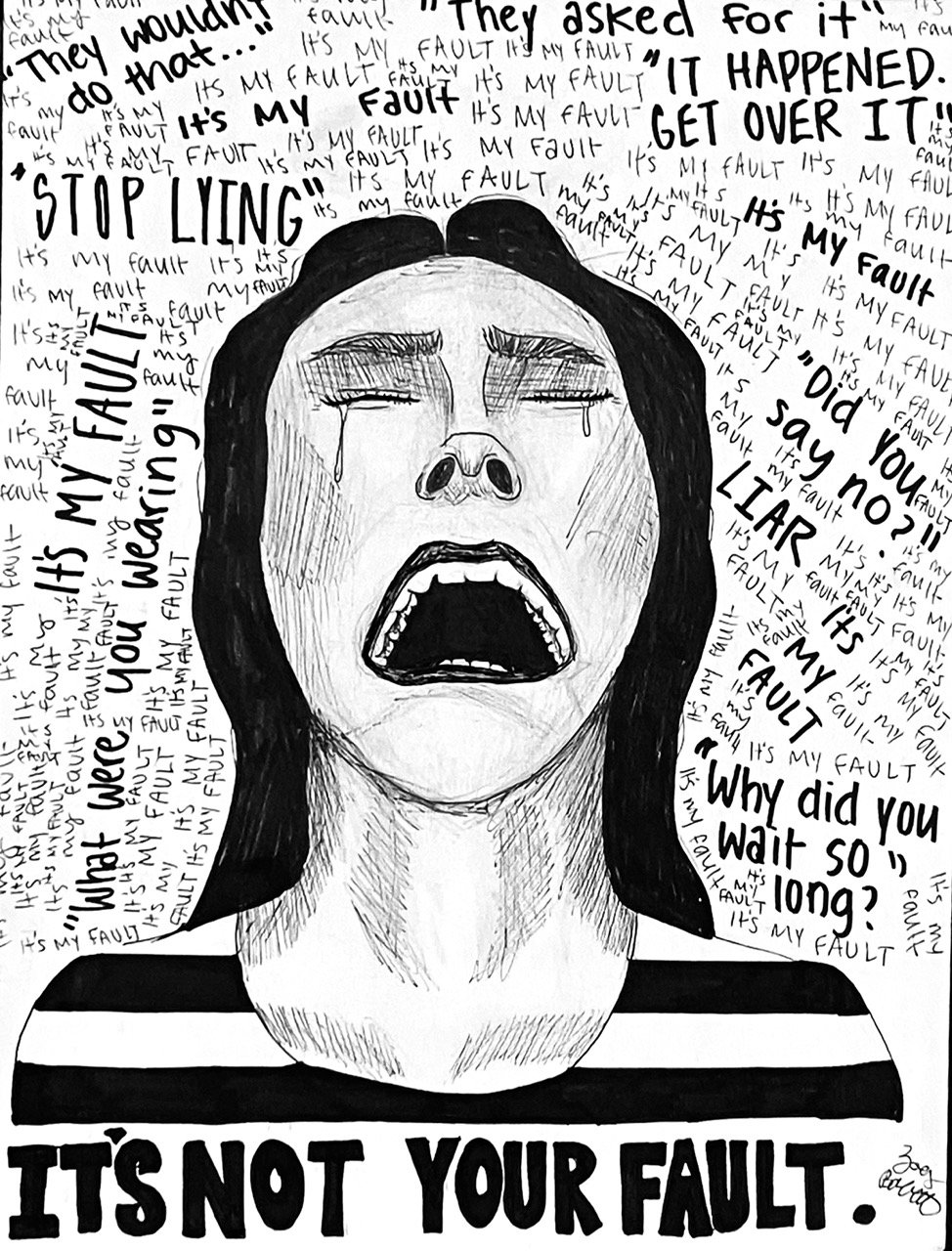

Image by artist: Zoey Barrett

Shortly after reading Chanel Miller’s memoir, Know My Name, I attended the Dayton, Ohio YWCA’s Sexual Assault Survivor Art Show. Miller’s account, plus a dozen individuals’ depictions of how their lives were adversely impacted by non-consensual sex illuminated how vulnerability and courage can lead to the empowerment of others.

I was reminded that one in four females are assaulted prior to age 18 in the US, that fewer than 5% of completed or attempted rapes against college women are reported to law enforcement,1 and that 67.5% of rapes are estimated to go unreported.2

Chanel Miller, known in the media for over a year as “Emily Doe,” was 22 and unconscious at a frat party in 2015 when sexually assaulted by 19-year-old Stanford freshman Brock Turner. At 1 AM on January 17th, two Swedish bicyclists spotted Turner violating Miller’s half-naked body on the ground behind a dumpster. They yelled at the perpetrator, who ran from the scene, but the Swedes caught up to and restrained him until law enforcement arrived.

In the ensuing media frenzy, the public learned that Miller was a college graduate working her first job. Turner was a 2012 record-holder from the London Olympic Trials and was attending Stanford on a swimming scholarship. Both were inebriated at the time of the attack.

Miller was transported by EMS to the hospital and when she regained consciousness, underwent an extensive victim examination. During her interview with a detective the next day, she learned that Turner had been released on bond by 11 PM the night of the assault.

Turner was originally charged with five felony counts: rape of an intoxicated person, rape of an unconscious person, sexual penetration by a foreign object of an intoxicated woman, sexual penetration by a foreign object of an unconscious woman, and assault with intent to commit rape. The rape charges were dropped when results of Miller’s rape kit were reported to authorities.3

Miller’s interviews with the rape crisis team and detective, and preparation for trial with the district attorney were further traumatizing, complicated by the fact that she recalled nothing of the assault.

Fourteen months after the assault, the jury found Turner guilty of three felony counts of assault with intent to commit rape of an intoxicated or unconscious person. He was sentenced to six months in the county jail, which translated to three months (every day of good behavior resulted in a day deducted from his sentence). The district attorney, Miller and her family, assault survivors, and much of the nation were outraged. The Victim Impact Statement Miller read to Turner prior to his sentencing was read by more than eighteen million people in Buzzfeed News over the next weeks.

Miller says she does “not write to trigger victims. I write to comfort them, and I’ve found that victims identify more with pain than platitudes.” She wants survivors to know what pressing charges entails, that their rage and anxiety are valid, that crisis teams are eager to assist, and that hope and joy are possible following sexual assault.

The legal drinking age across the US is 21, yet underage partiers have easy access to alcohol. Turner claimed to be an inexperienced drinker at the time of the incident and stated that he intended to establish a program for high school and college students in which he would caution them about the campus drinking culture and the promiscuity fostered therein. “I want to show that people’s lives can be destroyed by drinking and making poor decisions while doing so,” he wrote in a letter to the judge prior to sentencing.

Research indicates that alcohol use doesn’t cause sexual assault but can be a contributing factor. Approximately half of sexual assaults on college campuses involve a perpetrator, a victim, or both who had consumed alcohol.4

Over 97,000 sexual assault cases linked to drinking occur yearly on US college campuses. Tens of thousands more take place in households and neighborhoods unrelated to higher learning. The common denominator may be that victims who have been drinking are less able to defend themselves and less aware of what is happening around them.5

Mady DeVivo, Rape Crisis Center Manager at the Dayton YWCA, ended the “Art That Empowers” event by stating that the college culture of drunkenness must be addressed. Her flyer emphasized that sexual violence thrives when it is not taken seriously and victim blaming goes unchecked.

The defense attorney in the Stanford case epitomized victim blaming with questions about how much Miller had drunk at the party, what she was wearing, how many times in her life she had “blacked out,” whether she was sexually active, and whether she had a history of cheating on her boyfriend. He painted Miller as an irresponsible drunk and Turner as an innocent boy.

Turner never took responsibility for assaulting Miller, claiming instead that she had consented to the sexual encounter. Miller vehemently denied consenting and scoffed at Turner’s plans to offer prevention talks for students. She acknowledged that drinking was a major factor in her assault but stressed that consent and respecting women were the crux of the matter. To Turner’s claim that a night of drinking could ruin a life, Miller retorted that one night of drinking at the frat in 2015 collapsed both their lives.

As a result of Miller’s case, Aaron Persky, the judge ordering Turner’s six-month sentence, was voted off the bench in 2018. Furthermore, two bills were signed into law by California governor Jerry Brown: there is now a mandatory prison sentence for those convicted of assaulting an unconscious or intoxicated person, and the state’s definition of rape was expanded. Miller said of these developments, “I had done something good, created power from pain, provided solace while remaining honest about the hardships victims face.”

Chanel Miller resides, writes, and continues her visual arts work in New York and California. Brock Turner lives in Ohio where he is registered as a sex offender and works an entry level factory job. They would likely agree that the trajectory of both their lives was forever altered by those twenty minutes on the Stanford campus.

As a nation, we have a responsibility to educate youth about sexual assault prevention, how the consumption of alcohol increases one’s susceptibility to sexual assault and other injuries, and to demand stricter enforcement of drinking laws.

1 Fisher, B. S., Cullen, F. T., & Turner, M. G. (2000). The sexual victimization of college women. The National Criminal Justice References Services

2Truman, J. L., & Morgan, R. E. (2016). Criminal victimization, US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics

3 Miller, Chanel. Know My Name. New York: Viking, 2019.

4 Maryland Collaborative to Reduce College Drinking and Related Problems. (2016). Sexual Assault and alcohol: What the research evidence tells us. College Park, MD: Center on Young Adult Health and Development

5 The Recovery Village (2023). Alcohol abuse and sexual assault in college. The Recovery Village